Article

It’s a scenario every ISTDP therapist has encountered: a patient arrives with chronic pain, fatigue, migraines, or gastrointestinal issues. They’ve seen doctors. Tests have come back normal. They’ve been told it’s “just stress” or offered medication. But the suffering is real—and persistent.

As ISTDP clinicians, we’ve long understood that the body often carries unresolved emotional conflicts. That pain and physiological symptoms aren’t necessarily signs of disease, but of unprocessed affect, unconscious anxiety, and internal defense.

Now, emerging neuroscience is offering strong evidence to support this clinical reality. A recent study has uncovered a shared neural pathway in the brainstem that helps explain how the body and mind work together to signal danger—whether that danger is a physical wound or an emotional wound we’re not yet able to face.

The Research: CGRP Neurons and the Subparafascicular Nucleus

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2505889122

The study focused on a group of neurons in the subparafascicular nucleus (SPFp) of the thalamus. These neurons express calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a neuropeptide known for its role in pain transmission.

Researchers found that these CGRP-positive SPFp neurons:

- Receive direct input from the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, where pain signals first arrive.

- Are activated by mechanical, thermal, and inflammatory stimuli—classic pain inputs.

- When artificially stimulated, induce aversive emotional memory in animals.

- When genetically silenced, reduce animals’ observable pain behaviors—even when exposed to painful stimuli.

But here’s the key finding: these neurons are also involved in the brain’s response to emotional threat.

This means physical pain and emotional threat are processed by overlapping pathways, using a unified system designed to detect and respond to danger—regardless of whether it comes from outside the body or from within.

The Triangle of Conflict, Embodied

In ISTDP, we work with a model known as the Triangle of Conflict: unconscious feelings → anxiety → defenses.

When complex emotions—often rooted in early relationships—are triggered, they produce unconscious anxiety. If this anxiety becomes too intense or overwhelming, the ego deploys defenses to keep the emotion out of awareness.

One of the most common forms this takes is somatic disturbance. The body becomes the voice for what the conscious mind cannot yet process.

This study provides a biological substrate for that process.

If the nervous system encodes emotional threat in the same way it encodes physical injury, then it’s no surprise that patients feel real pain when difficult feelings begin to emerge. The body’s threat detection system can’t tell the difference between a broken bone and a broken heart. What it detects is danger—and it reacts accordingly.

In this way, the CGRPSPFp pathway may be a neurobiological correlate of the unconscious anxiety pathways that Davanloo and others observed clinically.

Understanding the Fragile Patient: Anxiety and Somatic Discharge

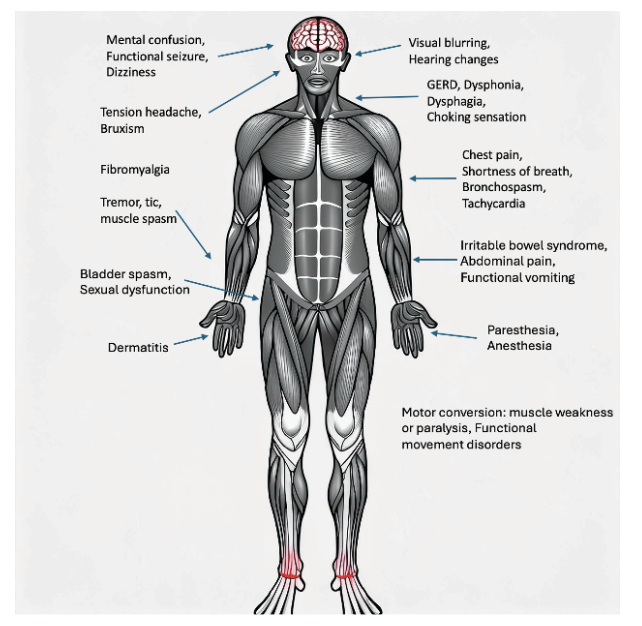

In ISTDP, we differentiate between pathways of anxiety discharge:

- Striated muscle discharge (felt as tension, shaking, panic)

- Smooth muscle discharge (felt as GI distress, bladder urgency, nausea)

- Cognitive-perceptual disruption (derealization, confusion, disorientation)

What this new research may be showing us is that the CGRPSPFp neurons are part of the smooth muscle/somatic anxiety system—helping explain why certain patients respond to conflict not with conscious emotion, but with physical symptoms.

This gives us a new way to understand the fragile patient, whose affect tolerance is limited, and whose threshold for anxiety overflow is easily breached. Their body becomes the battleground for unprocessed trauma. And the key to treatment lies not in managing the symptom, but in regulating anxiety, building capacity, and eventually allowing direct experience of feeling.

Somatic Symptoms Are Not Secondary

One of the most damaging assumptions in medicine and even parts of mental health is that if a symptom is psychosomatic, it’s somehow less real. ISTDP takes the opposite view: the symptom is real, the suffering is real—and it is often the most honest signal the patient can offer.

This study reinforces that position. These symptoms are not vague or imagined. They arise from real neural activation in the brain’s threat and pain circuits. The misinterpretation isn’t in the patient’s integrity—but in their nervous system’s attempt to protect them from unbearable affect.

This offers a compassionate, scientifically grounded way to work with patients who’ve been told they’re exaggerating or overly sensitive. We can now say, with confidence, that their body is doing exactly what it’s designed to do: protect them from danger. The problem is that the danger is internal.

Clinical Applications for Therapists

So what do we do with this as therapists?

First, we name the somatic signal. We validate the pain, tightness, nausea, or fog as meaningful communication—not something to push away.

Second, we track the dominant anxiety discharge pathway and help the patient recognize it. This calms the threat response in the nervous system.

Third, we work to restructure defenses. As anxiety comes down, we help the patient see how their psychological defenses may be keeping painful truths out of awareness, but also contributing to the very symptoms they suffer from.

Fourth, we help them access the underlying emotion. When rage, grief, or guilt is finally felt—not just talked about—the nervous system often no longer needs to signal danger.

Finally, we work to integrate meaning. When the patient begins to connect the dots between their symptoms and their emotional history, their sense of agency is restored.

In this way, ISTDP offers not just insight, but transformative healing. It addresses the root, not just the symptom. And now, we can say that this healing has a neural basis.

Final Thoughts: What the Body Already Knows

This research gives language to something ISTDP therapists already know through our clinical experience.

The body doesn’t lie. It remembers. It signals. It protects.

When we stop pathologizing the symptom and instead listen to it as a message from the unconscious, something shifts. We begin to see the patient not as broken, but as someone trying to survive—using the best tools their nervous system has available.

ISTDP gives us the tools to decode those signals. And neuroscience is beginning to show us that the process we guide patients through—recognizing defenses, regulating anxiety, accessing core feeling—may also be calming the brain’s most primal threat circuits.

This is where therapy meets biology. And the evidence is growing stronger: the work we do in the therapy room matters—right down to the level of the nervous system.