Article

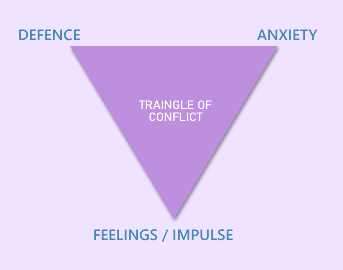

For half a century, Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy has been grounded in Habib Davanloo’s remarkable clinical observations. With thousands of hours of videotaped sessions, he showed how unconscious feelings surge upward, how anxiety is stirred, and how defenses rush in to block what feels unbearable. The “triangle of conflict” became our map: feelings → anxiety → defenses.

Every ISTDP therapist recognizes this process. We see it daily in the trembling of hands, the sudden sigh that escapes from the chest, or the blank, dissociated stare that silences a patient mid-sentence. But for all its power in practice, one question has long hovered: could these processes actually be measured scientifically? Could the phenomena that Davanloo tracked clinically also be captured in a laboratory, with instruments and data?

A recent project at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand set out to do just that. Lisa Chen’s thesis attempted to take ISTDP’s metapsychology into the laboratory, translating Davanloo’s theory of unconscious feelings, anxiety, and defenses into quantifiable science.

From Therapy Room to Laboratory

The research asked a radical question: Can the unconscious triangle of conflict be mobilized and measured experimentally?

Two studies were designed. The first tried to provoke complex feelings using very brief, masked picture presentations—subliminal flashes intended to stir the preconscious. The second shifted to a more direct method: showing emotionally charged film clips of separation between mother and child.

After these inductions, some participants were guided with ISTDP-style interventions: pressure to experience feelings, clarifications, and challenges to avoidance. Others received only supportive listening as a control.

The aim was simple yet bold: to see if unconscious feelings could be mobilized, and whether the anxiety pathways described by Davanloo would show up in measurable ways.

The Three Pathways of Anxiety in the Lab

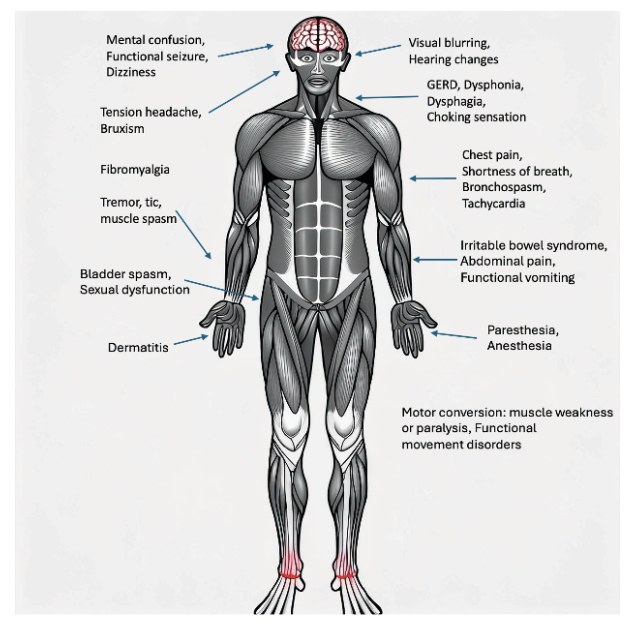

At the heart of Davanloo’s model is the idea that unconscious feelings are signaled through the body’s anxiety. But anxiety does not appear randomly—it follows distinct pathways.

-

Striated muscles: voluntary muscle tension in the arms, shoulders, chest, or face, often with sighing or trembling. This is the most adaptive pathway, allowing patients to stay present and explore feelings.

-

Smooth muscles: involuntary systems, producing nausea, migraines, irritable bowel symptoms, or shortness of breath. This reflects somatization and makes unconscious exploration harder.

-

Cognitive-perceptual disruption: sudden confusion, lapses of concentration, blurred vision, ringing in the ears, or dissociation. This is the most fragile form, where unconscious feelings threaten to overwhelm integration.

Every ISTDP therapist knows these markers in practice. Chen’s project attempted to quantify them in the lab.

Turning Anxiety Pathways into Scientific Data

Striated muscle anxiety—the tension that shows up in voluntary muscles—was tracked using electromyography (EMG) sensors placed on the forearm. These electrodes picked up tiny changes in muscle activation as participants were exposed to emotionally charged stimuli. Breathing was also recorded, and sighs were counted, since sighing is a classic marker of this pathway.

Smooth muscle anxiety—manifested in the body’s involuntary systems—was monitored through respiration and heart rate recordings. A chest belt measured breathing patterns, capturing shallow or irregular rhythms consistent with smooth muscle discharge. A pulse monitor tracked heart rate changes that accompany anxiety-driven activation of the autonomic nervous system.

Cognitive-perceptual disruption—the most fragile pathway—was evaluated both subjectively and objectively. Participants reported confusion or blankness on the newly developed Anxiety Discharge Questionnaire, while their performance on a Stroop task gave an objective measure. The Stroop required naming the color of printed words, and slower reaction times or errors reflected the lapses in concentration and cognitive disruption that ISTDP identifies.

Taken together, these methods transformed Davanloo’s pathways from clinical observations into quantifiable data. What had once been recognized by the therapist’s trained eye was now detected in muscle tension readings, breathing patterns, heart rate variability, sigh frequency, and changes in cognitive performance.

What They Found

The findings are as exciting as they are validating.

The questionnaire clearly separated into three clusters—striated, smooth, and cognitive-perceptual—mirroring Davanloo’s pathways. Physiological recordings confirmed the pattern: muscle tension and sighs tracked striated anxiety, breathing irregularities reflected smooth muscle anxiety, and Stroop performance faltered with cognitive disruption.

Perhaps most strikingly, the pathways correlated with defenses. Participants whose anxiety discharged through striated muscles also reported more mature defenses. Those whose anxiety went into smooth muscle or cognitive disruption reported more immature defenses and higher dissociation.

For ISTDP therapists, this is immediately recognizable. It confirms what we see in the room: anxiety pathways reveal something fundamental about a patient’s defensive structure and their capacity to tolerate unconscious feelings.

Why This Matters

For the first time, Davanloo’s metapsychology has been tested in the laboratory. The study provides quantitative evidence that anxiety pathways are not only clinical metaphors but measurable psychophysiological processes.

It also shows that ISTDP interventions—the moment-to-moment pressure to feel and the challenge to defenses—do more than stir surface emotion. They mobilize bodily and cognitive processes consistent with unconscious conflict breaking through toward consciousness. Supportive listening alone did not produce the same effects.

This is a breakthrough. It demonstrates that ISTDP is not only a powerful clinical method but also a model that can be validated by science.

A Bridge Between ISTDP and the Scientific Community

It means that the trembling hand, the sigh, the nausea, the sudden blank stare—all of these can now be shown to be measurable markers of unconscious conflict. It gives ISTDP therapists a new way to communicate with the wider scientific community, which often demands data and quantification.

It also hints at a future where clinical sessions could be paired with continuous physiological monitoring, providing moment-to-moment confirmation of what Davanloo observed so intuitively: the precise instant when defenses collapse, when unconscious feelings emerge, and when transformative breakthroughs occur.

Limits

This research is groundbreaking in showing that Davanloo’s anxiety pathways can be measured scientifically, but its limits must be noted. The participants were students, not clinical patients, and the emotional inductions (pictures and films) cannot replicate the complexity of a live therapeutic encounter. The measures—muscle tension, heart rate, breathing, Stroop tasks—capture important fragments but not the full relational dynamics of ISTDP. The new Anxiety Discharge Questionnaire is innovative, though still dependent on self-report. Overall, the study is a vital first step, but more work is needed in clinical settings to confirm its relevance for psychotherapy practice.

Final Reflection

Davanloo often insisted: “The unconscious does not lie.” What this research shows is that the unconscious also leaves measurable traces—in muscles, in breath, in cognitive performance—that can be captured by scientific instruments.

For ISTDP therapists, this is both validation and inspiration. The processes we track with such care are not only real but can now be documented and studied outside the therapy room. The laboratory has begun to catch up with what we have always known in practice.